Bryn is riding a trike when the bell rings for tidy-up time. He shouts ‘Oooooh!’ and hides behind a large tyre. Early years practitioner Naomi feels some irritation as she knows Bryn might refuse to move.

Taking a moment to empathise, she crouches down beside him and identifies his feelings: ‘I can see that you are feeling sad and angry that you had to stop riding the bike. You waited a long time for a go and now you feel cross and sad that you had to stop.’

Validating his feelings, she continues, ‘I would feel sad to stop doing something that I like, especially if I had to wait a long time.’

After Naomi proposes a solution – ‘We have to tidy up now. But would you like to have the first go on the bikes after lunch?’ – Bryn physically relaxes, says ‘okay’ and offers to help tidy up.

‘ATTUNE AND CONNECT’

Naomi is using an approach known as Emotion Coaching, a naturally occurring style of communication that was observed and labelled by US psychologist John Gottman in the late 1990s. Teachers, educational psychologists, health visitors and early years practitioners have been using an adapted version of the approach to support the development of children’s self-regulation skills for the past decade.

A new Education Endowment Fund (EEF) trial is now under way in 160 nurseries across England to look at the impact of Emotion Coaching on three- and four-year-olds’ self-regulation skills. Licette Gus, co-founder of Emotion Coaching UK (ECUK), who is delivering the trial with EEF, has trained and supported more than 20,000 adults across the UK, Europe, Asia and Australia.

She says, ‘When a child starts to experience a challenging emotion, Emotion Coaching supports the adult to “attune with” and “connect” with a child. The approach is grounded in relationships. It’s the space in between the adult and the child where the magic of Emotion Coaching takes place. This is the starting point from which a child can then move on to use more cognitive-based strategies.’

The observed outcomes of Emotion Coaching link to neuroscience, the physiology of stress and attachment theory. ‘Emotions and behaviour are inextricably linked. We cannot simply deal with behaviour without dealing with the emotions that give rise to behaviour,’ Gus says.

In the scenario above, early years practitioner Naomi verbally acknowledges and validates Bryn’s emotional state, which helps promote a sense of security. This activates changes in the neurological system which allow him to calm down, physiologically and psychologically.

Naomi says Emotion Coaching is ‘quicker than using adult insistence to bulldoze him into compliance’. She also says it helps her reflect on the importance of seeing the situation from the child’s perspective, rather than getting caught up in her own needs.

FOUR-STEP FRAMEWORK

Founders of ECUK, psychologist Gus, Dr Janet Rose and Dr Louise Gilbert, launched a four-step framework to Emotion Coaching in 2016, along with cascading model of training. The four steps include:

- Recognising the child’s feelings and emphasising with them: acknowledgement that the child is experiencing an emotional moment allows the necessary pause for thought and gives the adult the time to bear witness to the child’s emotions, tune into their own empathy and get ready to act in step two.

- Validating the feelings by labelling them: telling an angry child that you can see that they are angry may seem patronising and unnecessary. But research tells us that by naming the emotion the other person is feeling, we are encouraging the regulatory processes to engage and reconnecting the thinking brain with the limbic system. We are communicating that a) we understand how they are feeling and b) it is OK to feel like that. This is a vital step and without it, Emotion Coaching cannot take place.

- Setting expectations for appropriate behaviour, given the context: this allows you to put some limits on the behaviours, if necessary. A positive and empathic way of doing this is to state what is the acceptable behaviour or what you would like to see the child doing in this scenario. For example, ‘When we’ve had enough to eat, we can put our cutlery on the plate and take our plate to the sink’, rather than, ‘We do not throw food around the room.’

- Problem-solving with the child: the practitioner works with the child to consider what they could do when they feel those strong emotions next. For example, ‘I wonder whether it would be a good idea to go to the special beanbag in the corner next time you feel like this? Then I can come and help you figure out how to manage your frustrations.’

Emotion Coaching works with the ‘brain, body and emotions together’, Gus says. Using the framework gives adults the ‘calm and confidence’ to respond to a child experiencing strong emotions with the knowledge of why they are responding in such a manner. ‘The child is able to feel seen, soothed, safe and secure as a result of the adults interacting with them in an Emotion Coaching manner,’ Gus adds.

During the training, practitioners learn that their own emotional self-regulation is the precursor to them being able to support strong emotions in children. ‘They start to stop, pause and check on how they are feeling before attending to a child,’ Gus says.

REGULATION STATIONS

One setting that has embedded these principles into its practice is Zeeba Royal Arsenal Nursery in Woolwich, the first nursery to become an accredited Emotion Coaching UK provider. On a visit to the nursery last year, Gus says she was impressed with how each room, from baby to pre-school rooms, had a dedicated space related to emotions and learning about emotions.

She explains, ‘The Lavender calming corner in the baby room is a soothing, age-appropriate space with a backdrop of lavender fields; a soft purple rug and lavender-printed cushions. For one- and two-year-olds, there’s a reading area with emotion-faced cubes and pillows of real-life images of children printed on them. And toddlers can go to the Emotion Cottage, a place of calm, either alone or with an adult, to process and understand emotions.

‘Comfort Packs are given to each child when they start nursery to help them feel seen, soothed, safe and secure. The packs contain crochet pocket squares and scarves that their parent or carers are encouraged to wear before their child starts nursery. Their children also take sensory comfort from smelling their parents/carers when needed.’

Many nurseries have introduced calming corners or ‘zen tents’ where children and adults can go to read a book together or do a quiet activity. ‘This comes under step four of the programme,’ Gus says. ‘Emotion Coaching pulls together many of the strategies that are used to support PSED in the nursery. It acts as an umbrella under which many tools, such as breathing stars, emoji facial expressions or linking colours to emotions, can be usefully placed.’

But Gus points out that Emotion Coaching is not timetabled. ‘It happens in the moment when a child is dysregulated, so will take place anywhere in the nursery,’ she adds.

CO-REGULATION STRATEGIES

PHOTO Adobe Stock

In a busy nursery environment, there are so many factors that need focused attention that it can be easy to ‘forget about naming, labelling and validating’ emotions, Gus says.

‘By giving staff the tools and training, their meta-emotional philosophy – the way they think about feelings – shifts from an emotion-dismissing to a more Emotion Coaching one. This philosophical shift underpinning the change in practice helps support sustained and effective change.’

Nicky Shaw, ECUK trainer and former teaching fellow at the University of Strathclyde, says Emotion Coaching training helps support adults in the emotional environment of a nursery to regulate their own emotions so they can default to an empathetic position with the children.

In her previous role as a nursery teacher at a Scottish setting, Shaw wrote a thesis on Emotion Coaching in 2018. She says, ‘We realised that we had to build the foundations of emotional literacy for children when they were calm and not distressed. We used puppets, books, pictures of facial expressions, and we talked about emotions in everyday life. This teaching then enabled staff to use the five steps of Emotion Coaching with the children when they needed our empathic co-regulation.

‘The impact of this approach was profound. We started to see a decrease in dysregulated behaviour. Rather than addressing behaviour when the child is in a state of high emotion, we focused instead on what would make the child feel calm. We found that the more we did this, the more children began to approach staff to explain how they felt, and to experience co-regulation. Children then began to use their strategies to self-regulate.’

ECUK trial timeline: what’s next?

- January 2024: ECUK Early Years Project launched in collaboration with the EEF, the Stronger Practice Hubs and Norland College (the delivery partner)

- Nov 2024 – Jan 2025: Two-day online training course and monthly online two-hour training sessions

- Spring to summer 2025: Emotion Coaching to be used in everyday interactions with children

- September 2025: Randomised controlled trial with three- to four-year-olds in 160 settings (PVIs, maintained schools and nurseries)

- Autumn 2026: impact of the programme on children’s Personal, Social and Emotional Development evaluated and published by the National Centre for Social Research

Case study: Orchards Barns Nursery, Suffolk

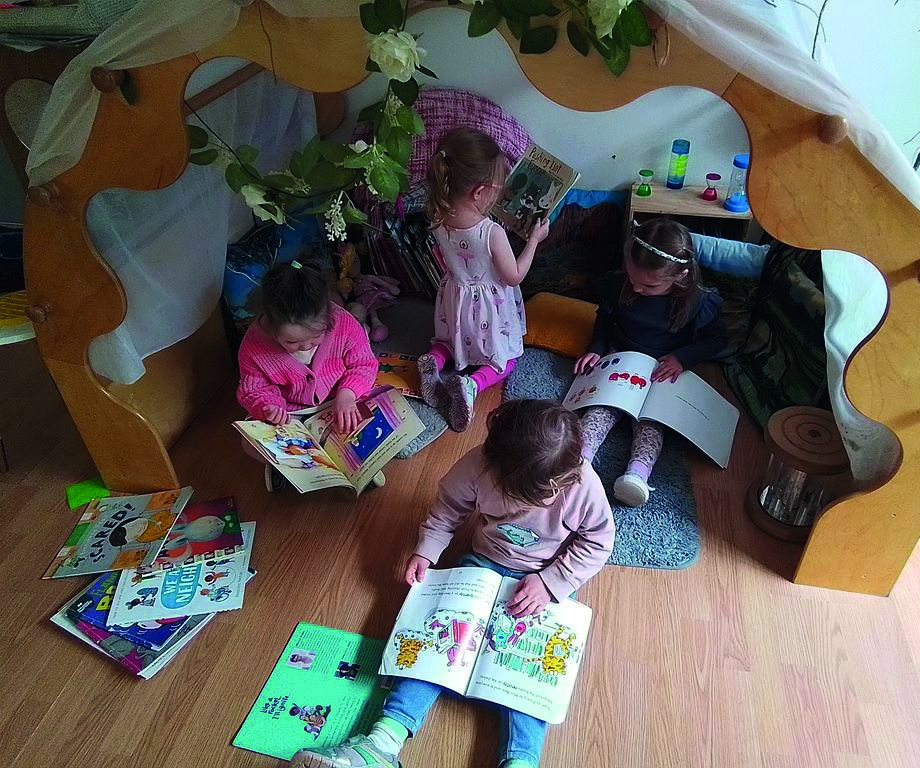

PHOTO Orchard Barns Nursery

Staff at Orchards Barns Nursery have been using Emotion Coaching with babies up to pre-schoolers since May 2021, after receiving a cascading form of training.

Nursery manager Diane Sexton says, ‘It’s helped us develop a deeper level of practice around emotional development and self-regulation. Understanding the theory of attachment and the importance of helping children develop self-regulation skills for their lifelong mental and physical health underpins our everyday practice.

‘The first step was to print out some A3-size Emotion Coaching scripts that we made and place them on the walls. These include prompts like: “I wonder if you’re feeling [sad, distressed, angry, fear, surprised, disgusted, joy] it’s OK to feel [emotion]”; “I would feel [emotion] too if that had happened”; “I understand, if my friend was playing with someone else I may feel [emotion] too.”

‘Using this language really helped in the baby room (up to two years), as previously practice mainly centred around either ignoring the behaviour and hoping it went away, correcting the behaviour, or pacifying children with cuddles and comforters and using phases like “you’re OK” and “stop crying now”.

‘Rather than thinking that paying attention to challenging behaviour encourages the persistence of that emotion, adults learn that distressed behaviour is communication of an emotion that the baby is experiencing, and needs support to manage. This is the shift from a judgemental to an empathic response, which is at the heart of Emotion Coaching.

‘The adults in the baby room now use co-regulation strategies to help the child soothe and calm, with the idea that over time the child will learn to regulate themselves. These include physical bodily experiences such as cuddling, rocking, stroking them to soothe, or perhaps putting a cool flannel on their forehead to help soothe the emotion.

‘They may use a soft, slow, low tone of voice, communicating to the baby they are safe and the adult is there. The adults may acknowledge that the baby is distressed by saying things like, “Oh, you’re crying such big tears, things really aren’t going well for you at the moment, I can see that, I’m here for you.”

‘We also changed the physical environment to support babies’ emotional needs. We bought a ceiling net and placed a cosy nest under it. Sensory cushions were added to the area to encourage softness and cosiness. The children can also hug, push against or punch them to release some of their energy. We added a book basket and some homemade sensory bottles. We printed and laminated pictures of sad, happy and tired faces.

‘The babies love the area, especially the books from the “That’s Not My” range, which include textures on each page that have a calming effect. Unsettled children now take themselves off to this area to calm down unprompted.’

PHOTOS Orchard Barns and Adobe Stock

MORE INFORMATION

- Early Years Emotion Coaching Project: emotioncoachinguk.com

- Nicky Shaw – University of Strathclyde: https://www.strath.ac.uk/staff/shawnickymrs

- The Hand Model of the Brain – an animated adaptation of Dr Dan Siegel’s original concept, ‘The Hand Model of the Brain’, aimed at children and young people, as well as the adults who interact with them: https://youtu.be/Kx7PCzg0CGE