Minimum staff to child ratios vary across the world – from none in Germany, Denmark and Sweden to 1:35 in Japanese kindergartens. In the UK, we tend to think that the fewer the children per adult, the better the care. Politicians are often tempted to use them as a lever to try to decrease childcare costs, with the DfE’s review of childcare delivery costs suggesting that nurseries could cut spending by as much as 15 per cent simply by working closer to ratio.

But this country’s ‘less is more’ rationale is not always shared – such as in Norway and Finland, which have a statutory maximum.

Each of the countries we examine here is under pressure from changes to its ratios, in both directions.

JAPAN

Japan’s population is shrinking – in 2014, the number of babies born slumped to just over the one million mark, and the total number of people was at a 15-year low. But after a concerted effort to expand daycare, a million more women are working since December 2012. Professor Mikiko Tabu, of Seitoku University’s Department of Professional Teachers in Matsudo, near Tokyo, says that while there is in theory enough nursery provision, there are issues with quality.

‘Each local authority has a duty to do checks, but the details of how often they do so is not known,’ she says. ‘Quality of service varies widely, and is generally poor for lack of public funding, as well as affordability.’

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Japan has a ‘highly educated’ early years workforce, with kindergarten staff qualified above the average for OECD countries, and ‘favourable staff-child ratios for zero to three-year-olds’. But staff-child ratios for three- to six-year-olds are ‘among the most unfavourable of the OECD’.

There are two types of setting: daycare and kindergarten, with associated qualifications of daycare centre educator and kindergarten teacher.

According to Miwako Hoshi, an early years education researcher, kindergarten is for three- to five-year-olds and lasts just four hours a day, using ‘child-led principles’. The ratio, which follows the primary school system, is ‘very high’ at 1:35.

The country’s high minimum daycare ratios have been unchanged for several decades.

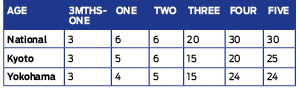

These are, per one adult:

Daycare is effectively the same service but more likely to be publicly subsidised, and includes babies to threes, for ten to 12 hours a day, six days a week. The regulations governing daycare describe it as ‘legally an institution of social welfare’, says Ms Hoshi. ‘The original concept of daycare is that it accepts children whose parents cannot take care of them during daytime. So, both for education and care, for three- to five-year-olds, more staff are needed than at kindergarten.’

Unlike in the UK, ratios can be improved at local government level. Ms Hoshi suggests that this ‘depends on the financial state of the city, and pressure coming from directors, or educators of daycare centres and the parents’, adding, ‘Educators of daycare centres often complain that the national legal ratios are too hard for staff. So if a city wants better quality daycare, it is possible to use a better ratio. Even if cities have the national ratio, they may have a better ratio in reality.’

Practitioners are qualified via a ‘licence’ to work in one or other of the systems, though more recently changes have been implemented to help them switch. It’s become common to find students training at universities for four years, to obtain a licence to practice. But as in the UK, poor pay is an issue.

‘The jobs of kindergarten teacher and daycare educator are not seen as unattractive for those who like children,’ says Ms Hoshi. ‘The problem is that practitioners often leave their job in three or four years because of low wages, especially in cases of private kindergartens. Some of them leave to marry, but some go to other jobs.’

Daycare educators in Japan receive at least two years’ training at specialist colleges. They study a broad curriculum covering early years education, physical education, arts and expression, natural environment and play, developmental psychology, and health. The training of kindergarten teachers also involves at least two years of training, key tenets being ‘child-centred education, the importance of play, learning through environment and holistic learning’, says Ms Hoshi.

Osamu Fujii, who runs a group of daycare centres in Kyoto, describes the numbers for over-threes as ‘startling’ to any onlooker. However, he says, this is simply a minimum standard required for granting a licence to the setting. On the ground, a better balance is often struck. In Kyoto, the local authority is well ahead of the curve, having upgraded its own three-year-olds ratio from 1:20 to 1:15 some 26 years ago.

Mr Fujii is in a relatively privileged position at his centre, Takatsukasa Hoikuen, which employs 23 full-time members of staff, many of whom are holders of both licences, across ten classes. He also uses a handful of part-time support staff, who are usually equally well qualified, meaning for children aged four and under, ratios are never higher than 1:8.

With more women in work comes more pressure on services, especially, according to Professor Tabu, as ‘more and more young parents are being forced to work longer hours because of low pay’. One solution is a new breed of care called ‘Nintei-kodomo-en’, which offers both timetables for children aged three and older, with a ratio of 1:15. To address the shortage of practitioners, local and central government is in the process of re-educating ex-educators who are out of work.

AUSTRALIA

According to Dr Kay Margetts, associate professor of early childhood at the University of Melbourne, the Australian system is heavily influenced by the UCL Institute of Education’s Effective Provision of Pre-School Education research. She says, ‘School readiness is not a key focus of our curriculum. We have a very strong focus on play-based learning.’

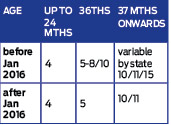

Australia’s ratios received an overhaul at the beginning of this year under the country’s National Quality Framework, which has ironed out many of the differing standards between states and territories. Ratios are, per one adult:

after Jan 2016 4 5 10/11

]]