Many children now enter formal education with reduced levels of proficiency in oral language. This is concerning, since well-developed oral language skills are strongly linked to academic achievement. However, the importance of oral language extends beyond academic success, impacting strongly on social, emotional and mental health and long-term outcomes. Children who come from disadvantaged backgrounds and who are English language learners (ELL) are at high risk of limited oral language skills. There are also concerns about the impact of cutting education budgets, as well as the Covid-19 pandemic and prolonged periods away from education settings, on children's language.

Alongside these issues, children with language difficulties are often at a double disadvantage, as research suggests education practitioners do not feel adequately skilled in supporting language needs (The Communication Trust, 2017). This is further worrying considering that Speech, Language and Communication Needs (SLCN) are the most prevalent area of education need in mainstream UK primary schools (Department for Education, 2017).

CURRENT CONTEXT

Oral language is a foundation for learning and achievement. However, many children struggle to develop oral language skills. At school entry in the UK, an estimated 7.6 per cent of children have clinically significant language disorders (Norbury et al., 2016). In economically deprived areas, 40 per cent of children are reported to have delayed language (Law et al., 2011), with the most economically deprived experiencing the most marked delays. Furthermore, closures of education settings because of the Covid-19 pandemic have widened the ‘language gap’, with two-thirds of teachers across primary schools reporting school closures negatively impacted language development in pupils receiving free school meals (Oracy All-Party Parliamentary Group [APPG], 2020).

Within the UK, the majority of these children are educated in mainstream education settings supported by education practitioners, whereas for those children with more complex needs, additional support is provided by speech and language therapists. However, there exists significant variation between geographical areas and within education settings as to how children with language needs are identified and supported.

Despite ongoing Government interest into how to support language needs (Bercow Review, 2008; Better Communication Research Programme, 2012), problems continue to permeate the system. Issues relating to the inequity of service delivery from speech and language therapy services are prevalent both within the UK and internationally, and tensions as to whether health or education sectors have primary responsibility for meeting the needs of children with SLCN are ingrained within the English system.

Further, while there has been significant interest in aiming to understand and enhance school provision for children with language needs, there continues to be challenges with how to achieve this in practice. Within the education system, special education provision, including for those children with language difficulties, is provided through a graduated response (SEND Code of Practice, 2015). There is an emphasis on whole-setting/class approaches and Quality First Teaching at a universal level (Tier 1) before providing more targeted (Tier 2) and specialised support (Tier 3). This tiered model is frequently used as a means of delivering language interventions within education settings, with interventions such as group language programmes, individual language programmes and speech and language therapy predominantly provided at Tiers 2 and 3 (Ebbels et al., 2019).

Although there is an established and increasingly growing evidence base of interventions which successfully support language through Tier 1 and Tier 2 delivery (Law et al., 2017), there is a paucity of evidenced-based interventions and approaches which are designed to be implemented at a universal level. Universal support of language difficulties has been found to be an effective means of improving language for children. However, for universal interventions to be effective, it is imperative that staff are highly trained and well- supported (Ebbels et al., 2019).

Indeed, the necessity of a highly skilled workforce has been frequently referred to (Bercow, 2018), yet there continues to be a wide variability in practitioner understanding and confidence in supporting language learning needs (APPG, 2021; Dockrell et al., 2017). While there is a request from practitioners for more training, there are a number of complex factors affecting how to translate training into more effective practice.

DEVELOPING EDUCATION PRACTITIONERS' SKILLS

Professional development (PD) for education staff can consist of a number of approaches (including, but not limited to, taught courses, attending conferences and professional learning networks), and there is significant variability in duration, intensity and participation. For education practitioners in the UK, as in other countries, it is part of teachers' standards as a minimum requirement to undertake PD to improve teaching. However, there are acknowledged challenges with how PD helps education professionals translate new ideas into practice, and the effectiveness of school-based PD to support language has limited evidence (Markussen-Brown et al., 2017).

Research has therefore focused on identifying those elements of PD which are considered to contribute to more effective outcomes, with the roles of coaching and mentoring being as important. Indeed, the inclusion of a coaching element to PD has been identified as resulting in improved language and literacy practices for teachers. While coaching is considered an important factor in effective PD, there is the question of who is best placed to provide coaching. Ebbels et al. (2019) suggest that coaching provided by speech and language therapists (SLTs) was not the most effective use of their input due to a limited understanding between teachers and SLTs about each other's roles and expertise. Further, coaching and mentoring can present additional challenges within schools and can require more support from school managers to be successful where it is not already established.

USING RESEARCH TO SUPPORT DEVELOPMENT

Despite the wealth of research in the area of language needs, gaps exist in our understanding of how to apply these research findings in education settings in a meaningful way. There continues to be a chasm between researchers' knowledge and practitioners' knowledge. The gap between research and practice has long been established, with many factors cited as barriers for research being implemented. These include data being collected but not used, an inability or lack of confidence to interpret findings, a lack of time or access to academic publications, and research evidence not being sufficiently transformed or mediated before it can be used in practice.

To overcome these factors, there has been a number of emerging methods aimed at developing more successful ways of implementing research findings. One approach is that of Knowledge Exchange (KE), which is described as a process that brings together academic staff, users of research and wider groups and communities to exchange ideas, evidence and expertise. KE recognises knowledge flow as a two-way process, with the emphasis on a collaboration between researchers and practitioners, and the iterative process that occurs from the original exchange and beyond. There is also considerable potential for KE as a means of developing evidence-informed practice within education settings. Our study aimed to contribute to the growing field and how it can be applied as part of a universal intervention which empowers educational professionals to enhance the oracy provision of their setting and thus support children's language development and overall learning.

SUPPORTING SPOKEN LANGUAGE IN THE CLASSROOM (SSLIC) PROGRAMME

Embedded within a KE framework, the Supporting Spoken Language in the Classroom Programme (SSLiC) aims for researchers and education staff to work collaboratively to investigate how the evidence base relating to communication and oral language that does exist might be applied to individual settings. The aim of SSLiC is also to investigate how the collective knowledge of researchers and education practitioners might be used to inform the wider community of what works to support children's oral language.

The SSLiC Programme was developed by researchers at the UCL Centre for Inclusive Education (led by Dr Bakopoulou) and sought to create a forum for KE between practitioners and researchers. The researchers served the role of facilitators within the programme and introduced practitioners to the evidence base available for supporting children's spoken language in early years settings and primary schools, as well as providing evidence-informed tools to audit the practitioners' settings' current strengths and areas for development. These tools included the Communication Supporting Classroom Observation Tool (CSCOT) (Dockrell et al., 2012) and an audit which identifies a setting's perceived strengths and areas for development.

The CSCOT has been recognised as a valid and reliable tool for informing practice for education professionals such as SLTs and psychologists (Dockrell et al., 2015), as well as classroom teachers (Law et al., 2019). Using the tools and supported by the SSLiC facilitator, the setting creates an action plan which identifies a SSLiC project to undertake.

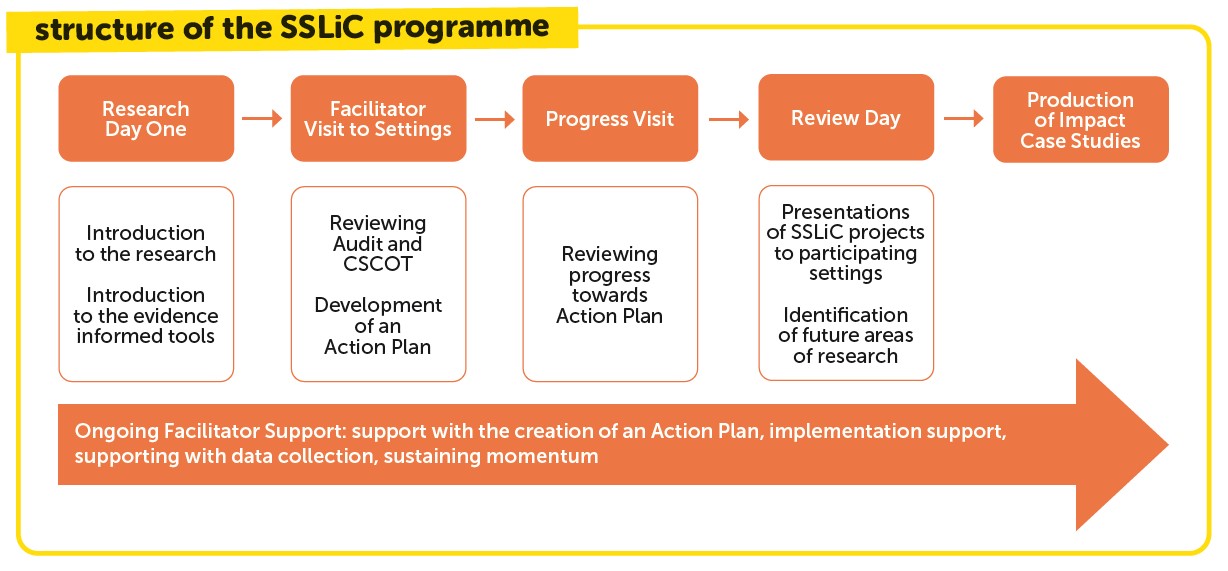

The SSLiC Programme aims to use practitioners' knowledge and their specific contexts, as it is recognised that successful change occurs in a unique context and system. The SSLiC Programme consists of activities over a period of time; the structure of the programme is shown below. As this illustrates, the final phase of the SSLiC Programme involves producing case studies for each participating setting, which aims to inform teaching practices, future research and further development of the programme.

As the programme has a unique approach of being embedded in KE, and given the imperative need to promote oral language in education settings, at a time when there is a paucity of universal language interventions, our study aimed to evaluate the implementation of universal language interventions in the context of the SSLiC Programme through addressing the following research questions:

What factors influence the implementation of universal language interventions in education settings (early years settings and primary schools)?

What factors influence the continued investment in the implementation of these interventions in education settings (early years settings and primary schools)?

The results of this study will be presented in the second article in this series, which will run in the June 2024 edition.

REFERENCES

Bercow J. (2008). 'The Bercow report: A review of services for children and young people (0-19) with speech, language and communication needs', Department for Children, Schools and Families.

Department for Education (2017). Statistical First Release: Special Educational Needs in England. DfE, London

Department for Education. (2015). Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years: Statutory guidance for organisations which work with and support children and young people who have special educational needs or disabilities. Reference: DFE-00205-2013.

Department for Education,(2012) Better Communication Research Programme. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yfjcx6z7

Dockrell, J.E., Howell, P., Leung, D., Fugard, A.J. (2017). 'Children with speech language and communication needs in England: Challenges for practice', Frontiers in Education, 2, 35.

Dockrell, J., Bakopoulou, I., Law, J., Spencer, S., & Lindsay, G. (2012). Developing a communication supporting classroom observation tool. London: Department for Education.

Dockrell, J., Bakopoulou, I., Law, J., Spencer, S., & Lindsay, G. (2015). 'Capturing communication supporting classrooms: The development of a tool and feasibility study', Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 31(3), 1-16.

Ebbels S., McCartney E., Slonims V., Dockrell J., Norbury C. F. (2019). 'Evidence based pathways to intervention for children with language disorders', International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 54(1), 3–19.

Law, J., Tulip, J., Stringer, H., Cockerill, M., Dockrell, J. (2019). 'Teachers observing classroom communication: An application of the Communication Supporting Classroom Observation Tool for children aged 4-7 years', Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 35(3), 203-220.

Law, J., Charlton, J., & Asmussen, K. (2017). Language as a child wellbeing indicator. Early Intervention Foundation.

Law J., McBean K., Rush R. (2011). 'Communication skills in a population of primary school-aged children raised in an area of pronounced social disadvantage', International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 46(6), 657–664.

Law J., Todd L., Clark T., Mroz M., Carr J. (2013). Early Language Delays in the UK.

Markussen-Brown, J., Juhl, C.B., Piasta, S.B., Bleses, D., Hojen, A., & Justice, L. (2017). 'The effects of language- and literacy-focused professional development on early educators and children: A best-evidence meta-analysis', Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38, 97-115.

Norbury C. F., Gooch D., Wray C., Baird G., Charman T., Simonoff E., Vamvakas G., Pickles A. (2016). 'The impact of nonverbal ability on prevalence and clinical presentation of language disorder: Evidence from a population study', Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57, 1247–1257.

Oracy All-Party Parliamentary Group. (2020). 'Speak for change: Initial findings and recommendations from the Oracy All-Party Parliamentary Group Inquiry', All Party Parliamentary Group.