The findings come from more than 10,000 staff from early years settings, primary and secondary schools and colleges responding to the National Education Union’s (NEU) latest survey on staff well-being, workload and retention during the last year.

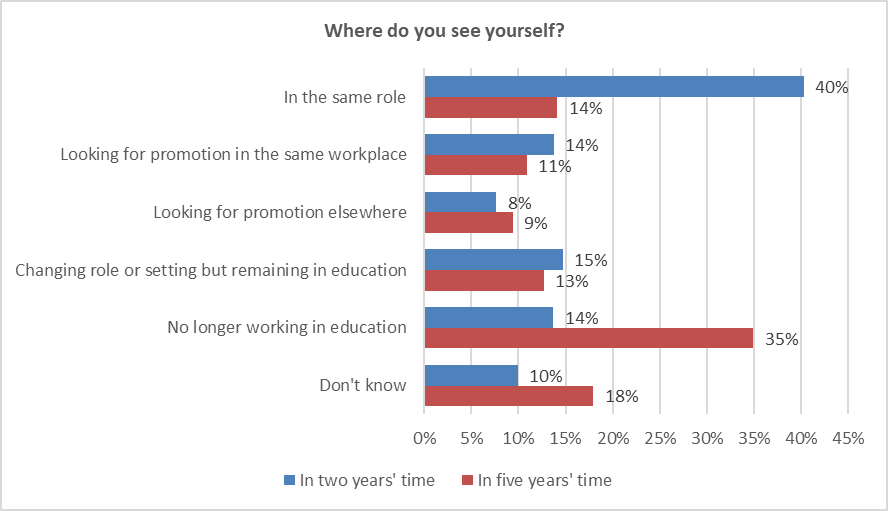

A worrying 35 per cent reported that they would no longer be working in education in five years’ time, with 53 per cent of them citing their reason as ‘the education profession is not valued or trusted by Government and/or the media’.

The survey of 10,696 NEU members was carried out between 2 to 10 March 2021 and is released today at the union's annual conference, which is taking place online this week (7 to 9 April).

Commenting on the survey results, Kevin Courtney, joint general secretary of the NEU, said, ‘It should come as no surprise that so many are thinking of leaving teaching. These findings come after a year in which the education profession – as key workers - have been provided few safety protections, had to improvise solutions where Government had simply left a void, and were met with a pay freeze for their troubles.

'To create an environment in which so many are overworked and looking for an exit, it is a scandal that so little effort has been made by Government to value the profession. Instead, they feel insulted, and for many there comes a point where enough is enough.'

When asked to compare aspects of their job to a year ago - to assess whether their job had improved or worsened over the course of the Covid year - two thirds (66 per cent), said it had got worse and just nine per cent believed it had improved.

Comments included:

'Stress. Mental well-being at work consists of a 10-minute mindfulness session rather than dealing with excessive workload or pointless data grabs.'

'I think that the expectations placed upon full-time teachers during the pandemic are immense.'

'Class sizes in primary schools are too large. The amount of work and professional scrutiny is not matched by the amount of PPA [planning, preparation and assessment time] provided to fulfil these duties.'

'The pandemic has highlighted a high expectation on teachers whilst a total lack of respect from Government.'

One in five respondents (20 per cent) said that their work-life balance was ‘much worse’ now than before the first lockdown. Seventy per cent said that workload had increased and almost all respondents - 95 per cent – reported that they were worried about the impact on their well-being.

However, 30 per cent reported that staff relationships with parents had got better over the past year, as they had been in greater contact with them during lockdown.

Retention

Despite the fact that 35 per cent of respondents were confident they would not be working in education in 2026, around three quarters (76 per cent) were still certain of seeing themselves in the profession in 2023.

The NEU said that uncertainty around the pandemic, and job opportunities inside and outside education, are likely factors for this.

Source: NEU survey

Of those who indicated they would no longer be working in education, either in two or five years’ time, the NEU asked them why. The most common response was that the education profession is not valued or trusted by Government/media (53 per cent), closely followed by workload (51 per cent), then accountability (34 per cent), and pay (24 per cent).

Workload and well-being

Respondents indicated that professional autonomy, student focus through smaller classes, and more staff in order to administer them, is a route to resolving the historic workload challenge.

But the NEU said that this must be matched by a Government willing to step back and allow a space for teachers, leaders and support staff to do their job. It would require less bureaucracy, fewer reforms, and a reduction in the culture of data and high-stakes tests, the union said.

When asked what could be done to improve well-being in the coming year, top of the list was the Government listening to the profession (56 per cent), followed by trusting the profession (39 per cent), a reduction in workload (51 per cent, and reducing the stress of external accountability including performance tables and inspections (50 per cent,) as well as internal accountability such as appraisal and observation (46 per cent).

Fifty one per cent of respondents said the receding of the pandemic would help, as would the additional work coming to an end (38 per cent), and confidence that one’s workplace is a safe environment to be in (45 per cent).

Mr Courtney added, ‘Let us be clear. Teaching is a fantastic job, and we should want to do everything we can to keep people in the profession who trained for it and saw it as a vocation in life. But it is the perennial issue of workload which is driving people out, and today’s survey shows that it is impacting on the well-being of almost all staff. Efforts to get working hours down were heading in the right direction in 2019 but were still stubbornly high – and the Department for Education was unwilling to budge on the main causes.

‘The solutions are perfectly clear to anyone willing to listen. It is the dead hand of Whitehall, of Ofsted and "data, data, data" which is getting in the way of a fulfilling working life for too many education professionals. Our survey shows it, the Government already knows this, and if they are to learn anything from an extraordinary year in education it should be this lesson from the leaders, teachers and support staff on the frontline.

‘Covid has proven that the roof would not fall in if Ofsted were told to step away. Ministers have said they will "trust teachers" when it comes to exams this year. Why not go further and take on trust their message that it is an overly bureaucratic system, of which the education secretary pulls the levers, which is driving people out of the profession.’