Intelligent materials’ is a term attributed to the pre-schools of Reggio Emilia in Italy, which use natural and recycled materials including fabrics, plastics, paper, clay and objects found in the environment. These materials are open-ended and can be used in a multitude of ways, with the potential to spark children’s creative thinking. For example, clay can be explored with hands, tools, mixed with water and made into many soft and squashy shapes, and then fired so as to become hard and permanent. Loose parts are also examples of intelligent materials because of their flexible and open nature.

Architect Simon Nicholson coined the term ‘loose parts’ in 1971, valuing them because of how they appealed to children’s enquiry. He included natural phenomena, such as gravity, light and magnetism, in this list of ‘variables’, saying ‘in any environment, both the degree of inventiveness and creativity, and the possibility of discovery, are directly proportional to the number and kind of variables in it’.

The more uses a material can have, the more intelligent we could say it is. Closed materials, such as pretend food made of plastic, reduce that wide potential, but they should not be discounted for play on that basis alone. Intelligent materials like blocks can be combined with more closed resources such as plastic food or cars to make structures which have meaning for the child and that bring their ideas to life.

Intelligent materials are often linked to critical thinking because they enable children to discover their own uses for them. For example, children at Ashmore Park Nursery in Wolverhampton used loose parts to represent their ideas about the African land snails they were learning to care for. They selected materials that were representative of the shape of the snails, and as they arranged the materials they imagined what the snails got up to when they were not watching. Materials of all kinds can narrate stories both invented by children or tales retold by them, as well as evoking memories (Pacini-Ketchabaw et al. 2017).

As teachers we have the responsibility to set the stage for education. Choosing specific materials is a skill. Materials are imbued with learning potential and expressive qualities. For example, which material would best suit the idea of expressing the dynamic qualities of water – large wooden blocks, clay, or paint?

We should go beyond making materials simply accessible in the environment to thinking about how materials might:

- meet with the children’s ideas, experiences or enquiries

- be presented and organised to invite connections to be made

- evoke memories, invite ways of using them or be used to narrate stories.

POSSIBILITY THINKING

Archie, 18 months, was playing with a treasure basket filled with an assortment of objects. He picked up two wooden egg cups, looking at them closely as if questioning what they were for before banging them together to create a loud sound. He was exploring them to find out what they could do; just as when children play with clay, paper or paint, they are problem-finding and problem-solving – posing the question ‘what if’ in multiple ways, or ‘possibility thinking’ (Craft 2000).

When possibility thinking is applied to intelligent materials, this questioning attitude goes from (non-verbal) expression of the idea ‘what is this material and what can it do?’ to gaining an understanding of how it can be used to experiment with ideas or communicate understanding.

To enable this creative shift from exploration to experimentation, we can think about how intelligent materials can be curated to:

- pose questions or problems

- enable connections and links

- imagine and explore possibilities.

CREATIVITY AS BOTH PROCESS AND PRODUCT

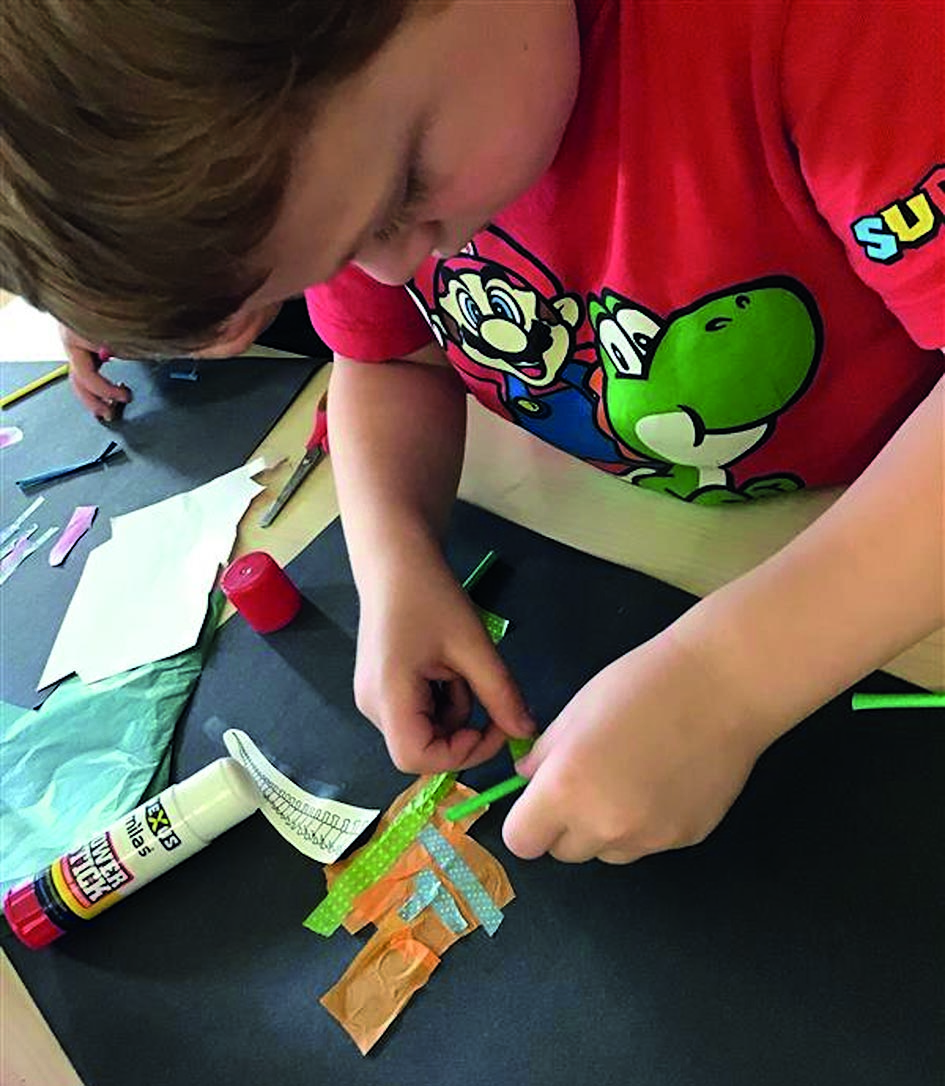

PHOTO Ashmore Park Nursery

Often, I see social media posts which declare that creativity and the arts are all about the process and not product. They are often accompanied with images of adult-designed templates that have been copied by children together with the alternative and messier amalgamation of marks or materials done by the child themselves. I am keen to stress I am not advocating for the use of adult-designed templates which deny children’s own creativity, but instead I challenge the binary viewpoint of process versus product. Both creative process and its outcome are present and simultaneous in children’s creative learning, I would suggest.

The creative process involves several steps that have been investigated and modelled by academics. According to Alane Jordan Starko of Teacher Education at Eastern Michigan University, USA, creative thinking patterns are associated with both process and outcome. It might begin with preparation, involving the gathering of resources and materials, perhaps as a response to an experience or problem identified. This preparation leads to a period of incubation, in which ideas begin to percolate and possibilities emerge through the exploration of the gathered material. This can be followed by moments of illumination where clarity is gained, and ways forward become more evident. Then, following illumination comes evaluation, perhaps in the form of testing out ideas and refining them. This occurs before implementation, in which what had been imagined, tested and evaluated enables the final idea to come to fruition.

This process of thinking is not always linear, and there can be lots of going backwards and forwards, but it is a process which leads to the eventual product.

For the child the product arising from this process may not be a physical one, but it could result in a connection between one thing and another –such as drawing the movement of a bird and comparing it to other things that fly. Products of creativity can be thoughts and new ways of doing things that have not been considered before. Creative thinking can also arise when children work together in a group. Creativity is a quality of thinking that is relational and social and occurs when children share ideas and grow their understanding via collaboration (Rinaldi 2006).

SUPPORTING CREATIVITY WITH INTELLIGENT MATERIALS

Whether Lego, charcoal, paper or mud, each material has its own ‘grammar’ – or set of characteristics (clay can be soft and malleable or hard and permanent). As this grammar is investigated by children, it is vital that educators respect the curiosity of the children’s minds and bodies – noticing what they do with their hands, and how this proceeds and links to their thoughts – rather than impose on them their adult approaches. When interacting, as educators we can:

- observe what children do to and with materials, noting the actions of the children and their responses to that material

- wonder alongside the children, verbalising ‘I wonder what might happen…’, etc.

- avoid having set goals or precise outcomes in mind.

Case study: the intelligence of paper

At Ashmore Park Nursery School in Wolverhampton, educators curated a collection of different kinds, weights and varieties of paper. They considered how these papers could be:

- Ripped and torn.

- Cut and shredded.

- Arranged and moved about.

- Folded and crumpled.

- Layered and combined with other materials.

Archie noticed how the papers could be layered on top of each other and, in doing so, ideas emerged about petals and flowers. Jackson and Olivia noticed how by cutting out different shapes and textures of papers, they evoked ideas about clothing, which prompted children to create people they imagined, knew or who featured in stories.

Educators noted how paper was a material holding high levels of curiosity and engagement for children and how in working around a table together, it wasn’t just about the sharing of resources but the sharing of ideas that emerged.

Reflection points

- What do you notice about children’s shift from exploration of materials to experimentation with possibilities?

- How could you curate materials to explore ideas, concepts or problems?

- How familiar are you with ‘the grammar’ of different materials you offer to your children?

REFERENCES

- Craft A. (2000) Creativity Across the Primary Curriculum. Routledge

- Cuffaro H.K. (1995) Experimenting with the World: John Dewey and the early childhood classroom. TCP

- Nicholson S. (1971) ‘How NOT to cheat children: The theory of loose parts’, The Landscape Architecture: https://tinyurl.com/aa2da7xp

- Pacini-Ketchabaw V., Kind S. and Kocher L. (2017) Encounters with Materials in Early Childhood Education. Routledge

- Rinaldi C. (2006) In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia. Routledge

- Starko J.A. (2021) Creativity in the Classroom. Routledge

Debi Keyte-Hartland is an early childhood consultant, artist- educator and MA tutor at CREC